Cesar Chavez, Walter Reuther, and the United Farm Workers of America Collection

Social movements that disrupt the status quo and go on to change the lives of participants most often coalesce around a powerful leader. In 1962, Cesar Chavez, a former migrant worker and community activist, began the long struggle for farm workers’ rights by organizing the National Farm Workers Association in Delano, California—the forerunner of the UFW. By 1965, after signing up about 1200 members, Chavez was asked to join a grape strike in Delano led by the predominant Filipino Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC).

The Walter P. Reuther Library commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Delano Grape Strike by recounting its near fifty-year relationship with the United Farm Workers to document and preserve its legacy.

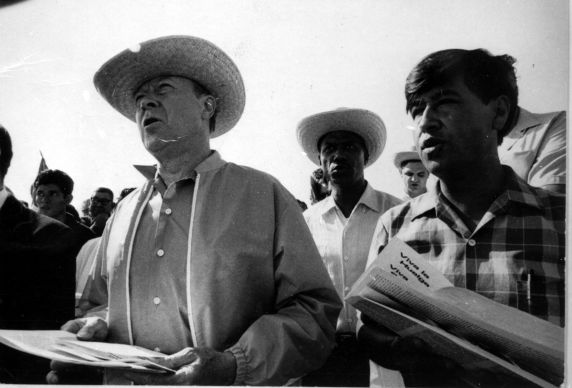

The 1965 grape strike and boycott—known as the Great Delano Grape Strike—catapulted Chavez into the national spotlight and attracted the attention of Walter P. Reuther, president of the United Automobile Workers Union (UAW). He too had battled injustice and fought for dignity and better working conditions for the industrial laborer. While attending the 1965 AFL-CIO convention in San Francisco, Reuther visited Chavez and AWOC leader Larry Itliong on the picket line in the little farming town of Delano with the local strikers. After Reuther’s firsthand experience in Delano, the UAW offered financial support and experienced staff to help organize and negotiate contracts. Chavez and Reuther remained close friends until Reuther’s untimely death in 1970.

The Walter P. Reuther Library at Wayne State University

The same year that Chavez established his farm labor organization, Walter Reuther, a former Wayne State University student, designated Wayne State University’s archives in Detroit, Michigan, to be the official repository for the UAW’s historical records. At the time, the archives was located in the basement of WSU’s main library. By 1966 UAW delegates approved financing the construction of a building on Wayne State’s campus honoring Reuther. He noted, “It is only through careful documentation of our history that an accurate account can be given of the UAW in our nation’s economic, political and social life.” The new building opened in 1975 and was dedicated to Walter Reuther and his legacy.

With the establishment of the Wayne State University’s archives as the UAW’s official records center, Reuther urged Chavez to preserve his records as well. He offered the Reuther Library as the official home for the UFW’s history as well. As Philip Mason, former director of the archives recounted, there were no public or private archives in California interested in the records of a farm worker organizer at that time because many believed the organization would not survive. In July 1967 the first installment of records was received in Detroit. This was the beginning of a fruitful relationship between the UFW and the Library.

Documenting and Preserving the UFW’s Mission—Peaceful Protest and Empowerment

With the UFW’s historical resources strategically placed in a world-renowned labor repository, access to the collection by local and remote users has been an easy process. Scholars who are interested in examining the written record have some familiarity with the collection as a whole, beginning with the Chavez presidential papers to the UFW departmental files. The UFW’s historical documentation includes numerous speeches given by Chavez and his co-founder Dolores Huerta; daily activity reports and diaries written by organizers and volunteers offer valuable insight into their daily lives during the national boycotts of the late 1960s and early 1970s; files relating to the opposition forces that attempted to disrupt the UFW’s mission of organizing farm laborers is prominent throughout the collection; and overwhelming evidence of public support in the form of letters sent by consumers who before the grape strike had no knowledge of the life of a migratory worker. As the UFW grew and gained national media exposure, such issues as child labor and pesticide abuse were brought to the public’s attention—all part of its mission to improve the lives of its members by protest and empowerment.

The collection yields a wealth of information in many areas of agricultural and social history. As the curator, I have been able to assist hundreds of researchers ranging in age from six to ninety six. The youngest inquirers are interested in Cesar’s words, so their educators request his speeches. A few of the older patrons were once child migratory workers following their families from ranch to ranch and desire anything from the collection that documents the life of child laborers in California. A young Latina preparing to graduate law school sought the names of those who visited Chavez during his first fast in 1968—thinking that her grandfather was among those who saw him weak in his bed—found a list of visitors that included her grandfather’s name. She remembered as a child hearing his stories of sacrifices that were made in order to educate the nation about migrant laborers. Another name penciled in on this list of bedside visitors was the young Rev. Jesse Jackson. During that same time period, the UFW collection contains a photocopy (not an original) of a telegram Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. sent to Cesar, offering support and praising his sacrifice.

Over the years I have made many friends and spent innumerable hours in conversation with inquiring patrons about the UFW’s history and legacy. I have had the great pleasure of working with a group of Latina university undergraduate students throughout one summer, assisting them with their assignments, as well as in-depth work with one scholar over the course of seven years in order to produce a book. I have learned from researchers that searching for the last piece of a puzzle sometimes will not make it complete. There are always more questions and speculation. For this reason, interested inquirers will continue to explore these primary sources for years to come.

This article is an adaptation of a work that originally appeared on the Reuther blog in March, 2014

Kathleen Schmeling is the UFW Archivist at the Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs. Pictured above: Walter Reuther and Cesar Chavez address striking farm workers.

- kschmeling's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn