Subject Focus: The Purple Gang

In the Winter 2012 semester, the Reuther Library worked with students in the Graduate Certificate in Archival Administration program at the Wayne State School of Library and Information Science to produce a series of student-written, guest blog posts.

Camille Chidsey is a Library and Information Science graduate student at Wayne State University. Her concentrations are in Archival Administration and Digital Content Management.

"'These boys are not like other children of their age, they’re tainted off color.' 'Yes,' replied the other shopkeeper. 'They’re rotten, purple like the color of bad meat, they’re a Purple Gang.'"

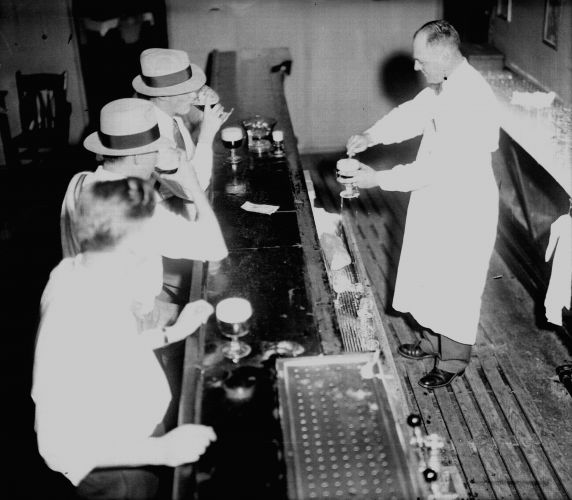

With the advent of Prohibition in 1918, the rise of criminal activity in the United States increased dramatically. Detroit was a center to these changes, as a result of the city’s proximity to Canada and the geographic ease of transporting illegal substances by waterway. Several police estimations have even suggested that as much as 75% of the liquor entering the United States came through Detroit by way of Canada. With smuggling so commonplace in Detroit, an environment where crime was not only permitted, but respected by shop owners, arose. Financial motivation spurred shopkeepers to invest in underground businesses, and by 1925 Detroit had approximately 25,000 Blind Pigs (speakeasies), and the number of gambling houses, opium dens, and brothels was high. These enterprises were run by mobsters, gunmen, drug peddlers, and hijackers, as well as organized gangs.

During this era, what became known as the Purple Gang rose to prominence in the Detroit area. Recognized as rulers of the Detroit underworld from 1928-1932, the Purple Gang was unique in that the majority of its members were teenagers. Most of the young Purple Gang members were children of Russian Jewish immigrants to Detroit. Individual Purple Gang members faced exclusion and segregation from an early age. The original core group of members was sent to the Old Bishop School, a separate school for unruly children in the Detroit districts who were evicted from other schools for truancy, fighting, delinquent behavior, or learning disabilities. Here they encountered isolation by being placed in the school’s Ungraded Section. Students in the other section of the school were referred to as the “normal students,” while their peers placed in the Ungraded Section were treated differently and not expected to improve.

Thus, the “outsider” mentality was formulated as a byproduct of religious and social ostracism. The roots of the Purple gang were formed. As children, the Purple Gang members focused on petty crime, mostly stealing food and money. Through the 1920’s as they grew up, they turned to more organized crime. The launch of Prohibition only furthered their efforts, securing their image as an indomitable force by 1928.

When bootleggers in Detroit smuggled liquor and beer into the city, they relied on frozen Lake St. Clair. The Purple Gang focused on hijacking the trucks and automobiles loaded with alcohol as they drove across the frozen water. Stopping the trucks and automobiles by gunpoint, killing the drivers, and stripping them of their loads became a signature sign of the gang. While they were never extremely organized, the loose confederation of predominantly Jewish gangsters exerted much force and instilled great fear in the community. The profits from bootlegging and rum running were high, and as their power, prestige, and pockets grew larger, the police turned a blind eye to much of their activity. They secured immunity from the Detroit police as increasing numbers of victims were afraid to testify against such a notorious and formidable gang.

As their reputation spread, other prominent Detroit gangsters joined the group. Individual men that had made headway within underground Detroit began to take on mentoring or even fatherly roles for the boys. In this way, the older Purple Gang members profited from delegating their responsibilities (often more dangerous ones) to younger, more impressionable members. In turn, many of the boys found the leaders and teachers they were looking for, as well as recognition for both themselves and their work. The increased unity and organization from the gang spurred local industries (and other bootleggers) to utilize the Purple Gang members for scare tactics.

Consequently, the Purple Gang became involved with several organized labor disputes, such as The Milaflores Massacre, The Collingwood Manor Massacre, and the Cleaners and Dyers War. The Cleaners and Dyers War was one of the early collaborative rebellions between the Purple Gang and a local industry. Occurring 1925-1928 in Detroit, this War was centered on labor strife in the laundry industry. Francis X. Martel, a local labor leader, was responsible for uniting tailor shops and drivers into an organized cleaning plants wholesaler’s organization. The Purple Gang was used to enforce union policy. Anyone who refused to join the laundry union had their employers’ plants vandalized and bombed, their union business agents murdered, employers forced out of business, and their employers’ clothing destroyed by dye. The Purple Gang’s role in the Cleaner and Dyers War eventually resulted in legal charges.

Cleaners who were hurt by the War were asked by Martel to file a complaint against Charles Jacoby, the ringleader of the operation with Martel and Abe Bernstein. Jacoby and Bernstein, mentors for the young Purples in the gang, were then tried for extortion (along with eleven other Purple Gang members) in a very public court case. All the members were acquitted, and the Purples celebrated their first legal victory.

Throughout their reign, the Purple Gang members continued to aid associations involved in anti-Prohibition efforts within the city. In this way, the gang was recognized both publicly and underground, as fear of the group’s growing power influenced several criminals to work with them, rather than against them. However, as the group gained momentum, inter-gang warfare emerged and jealousies, quarrels, and egos eventually caused the Purple Gang to self-destruct. By 1935, the Purple Gang largely disintegrated by murdering or betraying each other, leading to long prison terms with no hope of parole. It is estimated that over the course of their reign there were upwards of 150 prominent underworld characters associated with the Purple Gang. However, by 1933 they were no longer the dominant ethnic underground force, as Italian gangs gained supremacy. Independent Purples continued to operate from the early 1930’s-1950’s although their pack-based approach was no longer a characteristic or requirement of the organization.

For more information on this topic, please consult the Jewish Community Archives Leonard Simons Papers, JCA Small Collections, Prohibition in Southeastern Michigan image gallery, and the Reuther Library’s extensive audiovisual collections and Folklore Archive. The Virtual Motor City (VMC) is also an excellent resource for images related to local gangs and Prohibition in Detroit. This VMC portfolio contains Purple Gang images specifically.

- Public Relations Team's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn